About LAM

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis, usually known as LAM, is a very rare disease that affects women almost exclusively. It is characterised by lung cysts (air-filled sacs, which can affect breathing), abnormalities in the lymphatic system (which may result in collections of fluid in the chest and abdomen) and non-malignant kidney tumours (which can enlarge and bleed).

About LAM

Currently, around 350 women in the UK have a diagnosis of LAM. LAM appears to occur worldwide and to be equally rare in other countries.

Thirty years ago virtually nothing was known about LAM. Since then, clinical research across many countries has provided a great deal of information on how LAM affects women and the best ways to manage LAM. Studies investigating the underlying cause of LAM have led to a treatment which, whilst not a cure, slows the progression of LAM significantly in most women. So the outlook for women with LAM is now very much better than previously reported.

WHAT IS LAM?

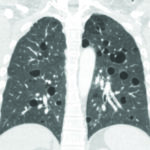

LAM is associated with a build-up of abnormal cells, known as LAM cells, particularly in the lungs, but also in the lymphatic system and kidneys. LAM cells are more likely to grow and multiply compared to normal cells, causing damage where they congregate. This leads to the development of cysts in the lungs, and these cysts have a characteristic appearance on a CT lung scan. LAM cells may also impair the flow of lymph in the lymphatic system and can cause benign (non-malignant) tumours in the kidneys.

LAM is associated with a build-up of abnormal cells, known as LAM cells, particularly in the lungs, but also in the lymphatic system and kidneys. LAM cells are more likely to grow and multiply compared to normal cells, causing damage where they congregate. This leads to the development of cysts in the lungs, and these cysts have a characteristic appearance on a CT lung scan. LAM cells may also impair the flow of lymph in the lymphatic system and can cause benign (non-malignant) tumours in the kidneys.

The name lymphangioleiomyomatosis reflects the different components of the disease. Lymph and angio refer to the lymph and blood vessels that are involved, and leiomyo refers to smooth muscle cells which LAM cells resemble.

LAM that occurs on its own is sometimes called sporadic LAM to distinguish it from LAM that can occur in people with a condition called tuberous sclerosis (TSC-LAM, see below). Unlike TSC, sporadic LAM cannot be inherited or passed on to children.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF LAM?

LAM affects different women in different ways, and the rate of progression shows considerable variation between women. Some women with LAM have no or very mild symptoms, whilst others have troublesome symptoms from early on.

Common symptoms include:

- breathlessness, particularly on exertion – this is usually due to cysts taking up space in the lungs and also airway narrowing, but it can also be due to a chylous pleural effusion – see below

- fatigue – some degree of fatigue is common in LAM

- chest pain – many women with LAM experience twinges of chest pain from time to time; causes include infections or scar tissue from previous procedures. More severe or protracted pain may suggest a pneumothorax – see below

- wheezing

- cough – this may be associated with LAM, or with infections. Blood or lymph may be coughed up if blood vessels or lymph channels in the lung are affected

- abdominal bloating, swelling and discomfort occur in some women

WHAT ARE THE COMPLICATIONS OF LAM?

Problems relating to LAM include:

Problems relating to LAM include:

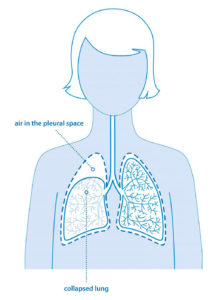

- Pneumothorax (Collapsed Lung) A pneumothorax is common in LAM with around three-quarters of women having at least one pneumothorax at some time. It occurs when a cyst bursts and air leaks into the pleural space around the lung. Symptoms usually include chest or shoulder pain associated with breathing, and a rapid increase in breathlessness. For many women it is the first sign of LAM.

- Angiomyolipomas (AMLs) These are benign (non-malignant) tumours, usually occurring in the kidneys. Around half of women with LAM will have an angiomyolipoma. Most are small and don’t cause symptoms, but they can bleed, particularly those over 4cm in diameter. They can be detected by CT scan, MRI scan or ultrasound.

- Chylous pleural effusion Although less common, LAM cells can block lymph flow in the lungs causing milky fluid to gather around the lung, known as a chylous pleural effusion, leading to breathlessness. Occasionally some lymph is coughed up as sticky, whitish phlegm.

- Abdominal LAM Two-thirds of women with LAM have enlarged abdominal lymphatics. This usually causes no symptoms but around 10% have abdominal symptoms such as bloating.

For treatment of these complications, please see below.

WHO DEVELOPS LAM AND WHY?

LAM is extremely rare. Sporadic LAM affects around 10 in every million women in the UK. Sporadic LAM is not inherited and it is not passed on to children. However, LAM may occur as part of tuberous sclerosis (TSC), namely TSC-LAM. Tuberous sclerosis is an inherited condition and so people with TSC-LAM can pass TSC on to their children. This is an important distinction. Although LAM is common in adult women with TSC it is often mild and may cause few symptoms.

The cause of sporadic LAM is still unknown, but the condition almost exclusively affects women. It is thought that this may relate to the female hormone oestrogen. LAM cells respond to oestrogen by growing more quickly and spreading around the body. Therefore, increased oestrogen levels – whether arising because of pregnancy or oestrogen-containing medication – may cause LAM to progress more rapidly. After the menopause, the progression of LAM is usually more gradual.

The first symptoms of LAM usually appear in women between the ages of 20 and 50. The diagnosis may not be confirmed for some time because many of the symptoms of LAM are similar to those associated with conditions such as asthma. Today, the delay in diagnosis is less than it was, due to greater awareness of the condition and the increased use of CT scans. In the early days a diagnosis was usually made after a pneumothorax or the development of breathlessness whereas more recently a diagnosis is more likely to be made after a pneumothorax or as an incidental finding on a CT scan before breathlessness is apparent.

HOW IS LAM DIAGNOSED?

Symptoms, chest X-rays and breathing (lung function) tests may suggest LAM, but the diagnosis is usually confirmed by finding typical cysts in both lungs on a CT lung scan. A raised blood level of a LAM-related protein, called VEGF-D, is also used as a diagnostic pointer for LAM. A diagnosis of LAM can usually be made on the basis of these tests, particularly if a patient has kidney tumours or tuberous sclerosis. If there is any doubt however a lung biopsy may be required. This is usually carried out through a small incision in the chest under a general anaesthetic.

LAM AND TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS COMPLEX (TSC)

Most women presenting with LAM do not have TSC, and when TSC is present it has usually been obvious from childhood. TSC is generally associated with unusual skin changes, tumours in other organs and sometimes epilepsy, learning and behavioural problems. Very occasionally people with TSC have a very limited form of the disease and few medical problems, so the diagnosis may be overlooked for some time. For these reasons some women with LAM may need genetic tests to ensure they do not have a mild form of TSC in association with LAM. The inherited nature of TSC is very relevant when considering pregnancy since 50% of children will inherit TSC. (See LAM Action leaflet on LAM and pregnancy).

WHAT HAPPENS AS TIME PASSES?

LAM is a progressive disease although, in the absence of treatment, progression is usually slow with a gradual decline in lung function and increase in breathlessness over time. The rate of progression varies considerably between individuals and current research is trying to identify the reasons for this variation.

There was a very significant breakthrough for women with LAM around 2010 when it was discovered that the drug sirolimus (also known as rapamycin, trade name Rapamune) can slow the decline in lung function in most women with LAM. Use of sirolimus has had a very positive impact on the progression of LAM for many women, and quality of life, severity of symptoms and survival rates have improved as a result. A few years ago, 90% of women were alive 10 years after being diagnosed with LAM, but with the increased use of sirolimus this figure has improved significantly and is likely to improve further.

HOW SHOULD WOMEN WITH LAM BE MONITORED?

Women diagnosed with LAM should be monitored regularly and this will include lung function tests. The tests most relevant for LAM are the FEV1 (which sees how quickly you can empty your lungs by measuring the volume of air you can blow out in one second) and the TLCO / gas transfer test (which sees how well your lungs are able to take up oxygen from the air you breathe). Kidney scans will monitor whether angiomyolipomas are present and how big they are; larger angiomyolipomas tend to grow faster and are at greater risk of bleeding. Pneumothorax, infections and other problems should be monitored and treated as symptoms dictate.

WHAT TREATMENT IS THERE? - Treatment for LAM & its symptoms

Treatment for LAM & its symptoms

- Inhalers – Many women with LAM find that bronchodilator inhalers such as salbutamol (Ventolin) help to reduce breathlessness. Longer-acting bronchodilators are often used in preference now. Some inhalers contain two long-acting bronchodilator drugs with different mechanisms of action; one benefit is that such inhalers only need to be taken once a day. For some women this is the only treatment needed.

- Sirolimus – Although there is no cure for LAM yet, the drug sirolimus (also known as rapamycin, trade name Rapamune) is a very effective treatment, slowing the rate at which lung function declines and reducing the size of kidney angiomyolipomas (AMLs). It is now used frequently for women with progressive disease or complications such as a chylous effusion. Therefore, women with suspected LAM should be referred to a specialist with experience of using sirolimus in patients with LAM for appropriate assessment, treatment and monitoring.

- Supplemental Oxygen – When breathlessness becomes more troublesome or oxygen levels fall, breathing additional oxygen may help. Oxygen can be given from oxygen cylinders or from a machine called an oxygen concentrator, which extracts oxygen from the air. Small, easily portable oxygen systems are also available which help people remain active.

WHAT TREATMENT IS THERE? - Treatment of Complications of LAM

Treatment of Complications of LAM

- Pneumothorax (Collapsed lung) – A pneumothorax is usually a sudden event and needs hospital treatment. It is normally treated by sucking the air out of the space around the lung with a needle or tube inserted under a local anaesthetic. Sometimes an operation called a pleurodesis is recommended. The aim of a pleurodesis is to stick the outside of the lung to the chest wall to prevent the lung collapsing again.

- Angiomyolipomas (AMLs) – Around half of women with LAM will have a benign tumour in the kidney called an angiomyolipoma. Most are small and don’t cause symptoms, but occasionally larger tumours cause pain or bleeding and they may need to be treated. Sirolimus and a related drug, everolimus, are effective in reducing the size of AMLs. For larger AMLs and for AMLs that are bleeding other treatment may be needed, namely embolisation or occasionally surgery to remove the AML. With embolisation, the blood supply to the AML is blocked, causing it to shrink and also prevent bleeding. This is done through a catheter inserted into the artery to the kidney and does not normally need a general anaesthetic. The aim of treatment is to preserve as much normal kidney as possible, and avoid removing a kidney unless there is no alternative.

- Chylous pleural effusion – Lymph that forms in the digestive system, called chyle, sometimes builds up in the pleural cavity around the lungs and causes breathlessness. The fluid can be removed, and sirolimus can usually prevent chyle from re-accumulating. If it does build up again a pleurodesis may be considered.

WHAT TREATMENT IS THERE? - Lung Transplant

Lung Transplant

Lung transplantation may be an option for some women with very advanced LAM, where no other treatment options are possible. Some women with LAM in the UK and others around the world have had successful lung transplants. However, the benefits seen from the use of sirolimus has reduced considerably the number of patients requiring a lung transplant.

WHAT TO DO IF YOU DEVELOP NEW SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of pneumothorax (collapsed lung) include:

- Sudden, sharp chest or shoulder pain, often worse when breathing

- Sudden increase in breathlessness

Symptoms of bleeding from a kidney angiomyolipoma (AML) include:

- Sudden, usually severe, pain in the abdomen, flanks or back

- Dizziness when you stand up

- Blood may be seen in your urine

If you develop any of the above symptoms YOU SHOULD GO TO HOSPITAL STRAIGHT AWAY

RESEARCH & HOPES FOR THE FUTURE

Research has made an enormous difference to our knowledge of LAM, in establishing optimum management for women with LAM and for understanding the underlying cause of LAM. It is responsible for the discovery of sirolimus and the clinical trials that showed that the drug was effective in women with LAM. The success of this programme is due to the excellent collaboration between research workers in different countries, to the establishment of registries of patients with LAM and to the way that basic scientists, clinicians, patient and self-help groups have worked together; the latter include LAM Action in the UK, the LAM Foundation in the US, and similar groups in other countries.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL CENTRE FOR LAM

The UK National Centre for LAM was established in April 2011 by Professor Simon Johnson at The Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. It is a nationally commissioned service of the NHS.

The centre delivers specialist clinical care for women with LAM and suspected LAM. It is designed to help ensure timely diagnosis and best management of all aspects of LAM, either exclusively at the centre or in partnership with local providers. Although independent from LAM Action, women with LAM are clear beneficiaries of the centre and feedback from those who attend the centre is very positive.

In conjunction with the University of Nottingham, the LAM centre is also a hub for clinical trials of new therapies for LAM, the evaluation of biomarkers, and laboratory research into the molecular basis of the disease.

Referrals to the National Centre for LAM should be made through a medical practitioner wherever possible.

Contacts

Tel: 0115 970 9322

Email: nuhnt.lamcentre@nhs.net

DOWNLOAD OUR LAM FACTSHEET

To download a copy of our LAM Factsheet, please click here.